One of Graziani’s main themes runs as follows. In order to finance production, the entrepreneur must obtain the funds necessary to pay his workforce in advance of sales taking place. Starting from scratch, he must borrow from banks, at the beginning of each production cycle, the sum which is needed in order to pay wages, creating a debt for the entrepreneur and, thereby, an equivalent amount of credit money, which sits initially in the hands of the labour force. Production now takes place and the produced good is sold at a price which enables the debt to be repaid inclusive of interest, while hopefully generating a surplus – that is, a profit – for the entrepreneur. When the debt is repaid, the money originally created is extinguished. An entire monetary circuit is now complete.

This account of the monetary circuit has a number of extremely important and distinctive features. It emphasises, in particular, that a) there is a gap in (historical) time between production and sales which generates a systemic need for finance; b) bank money is endogenously determined by the flow of credit and c) total real income must be considered to be divided into three parts – that received by entrepreneurs, that received by labour and that received by banks. We have already travelled an infinite distance from the (yes, silly) neo-classical world where production is (must be) instantaneous, where money must be exogenous and fixed and has no counterpart liability, and where the distribution of income is determined by the marginal products of labour and capital – a construction which depends entirely on the assumption that all firms sit perennially on a single aggregate neoclassical production function frontier.

− Wynne Godley, Weaving Cloth From Graziani’s Thread in Money, Credit And The Role Of The State: Essays In Honour Of Augusto Graziani

Tag Archives: wynne godley

Some Nice Words On Wynne Godley And Monetary Economics

I am reading this book The Oxford Handbook of Post-Keynesian Economics, Volume 1: Theory and Origins and it has some nice chapters!

In his chapter Postkeynesian Precepts For Nonlinear, Endogenous, Nonstochastic, Business Cycle Theories, K. Vela Velupillai has some nice words on Wynne Godley and his book Monetary Economics co-authored with Marc Lavoie:

Flow Of Funds And Keynesian Macroeconomics

The subject of money, credit and moneyflows is a highly technical one, but it is also one that has a wide popular appeal. For centuries it has attracted quacks as well as serious students, and there has too often been difficulty in distinguishing a widely held popular belief from a completely formulated and tested scientific hypothesis.

I have said that the subject of money and moneyflows lends itself to a social accounting approach. Let me go one step farther. I am convinced that only with such an approach will economists be able to rid this subject of the quackery and misconceptions that have hitherto been prevalent in it.

– Morris Copeland, inventor of the Flow Of Funds Accounts of the United States, in Social Accounting For Moneyflows, in Flow-of-Funds Analysis: A Handbook for Practitioners (1996) [article originally published in 1949]

Alas monetary myths continue to exist. The above referred handbook was published in 1996 starting with Copeland’s 1949 article and the editor of the book John Dawson himself had an explanation of why myths continue to exists despite some brilliant work such as that of Copeland. In page xx, Dawson says:

the acceptance of… flow-of-funds accounting by academic economists has been an uphill battle because its implications run counter to a number of doctrines deeply embedded in the minds of economists.

In a recent blog post blog post Paul Krugman is dismissive of Wynne Godley’s approach to macro modeling and instead appeals to some Friedmanism. Perhaps Dawson’s quote explains why this is so. However it may not be the only reason, given how Krugman has shown some tendency to be heteredox in recent times but his latest post ends all doubts and we can say he is highly orthodox. And that other reason is professional turf-defence.

Also, Krugman was writing in response to an NYT article Embracing Wynne Godley, an Economist Who Modeled the Crisis highlighting the importance of Wynne Godley’s work. That article was by a journalist who was perhaps unaware of the history of Post-Keynesianism. But Krugman himself dodged Godley’s work as “old-fashioned” – as if there is something fundamentally wrong about old-fashion and as if economics should proceed by one fashion after another.

A bigger disappointment is that Krugman failed to acknowledge that there has existed a heteredox approach since Keynes’ time. As Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie begin Chapter 1 in their book Monetary Economics:

During the 60-odd years since the death of Keynes there have existed two, fundamentally different, paradigms for macroeconomic research, each with its own fundamentally different interpretation of Keynes’ work…

And Krugman’s usage of the phrase old-fashioned hides the fact that this is so.

Back to Copeland. In the same article Social Accounting For Moneyflows, Copeland is clear about his intentions and the direction he is looking:

When total purchases of our national product increase, where does the money come from to finance them? When purchases of our national product decline, what becomes of the money that is not spent? What part do cash balances, other liquid holdings, and debts play in the cyclical expansion of moneyflow?

Copeland’s analysis was not simply theoretical. It led to the creation of the flow of funds accounts of the United States and the U.S. Federal Reserve publishes this wonderful data book every quarter. Although, Copeland was simply looking and proceeding in the right direction, it can be said that a more solid theoretical framework to build upon Copeland’s brilliant work was still waiting at the time.

Of course, in the world of academics, there already existed two main schools of thought very hostile to one another. Keynes’ original work contained a lot of errors and for most economists, a bastardised version of Keynes’ work became the popular understanding. It was however the Cambridge Keynesians who founded the school Post-Keynesian Economics who believed they were true to the spirit of Keynes and this led to a parallel body of extremely high-quality intellectual work which continues to this day – and still dismissed by economists such as Paul Krugman. Of course, in this story, it should be mentioned that there was a Monetarist counter-revolution mainly led by Milton Friedman who was trying to bring back the old quantity theory of money doctrines and was “successful” in permanently distorting the minds of generations of economists to date. Greg Mankiw is quite straight on this and according to him, “New Keynesian” in the “New Keynesian Economics” is a misnomer and it should actually be New Monetarism.

Interestingly, one of Morris Copeland’s ideas was to show how the quantity theory of money is wrong. According to Dawson (in the same book referred above):

[Copeland] himself was at pains to show the incompatibility of the quantity theory of money with flow-of-funds accounting.

Meanwhile, in the 1960s and to the end of his life, James Tobin tried to connect Keynesian economics with the flow of funds accounts. While a lot of his work is the work of a supreme genius, he couldn’t manage. Perhaps it was because of his neoclassical background which may have come in the way. According to his own admission, he couldn’t connect the dots:

Monetary and financial data, so far as they are based on institutional balance sheets and prices in organized markets, are abundant. Modern machines have made it possible to improve, refine and expand the compilation of these data, and also to seek empirical regularities in financial behavior in the magnitude of individual observations. On the aggregate level, the Federal Reserve Board has developed a financial accounting framework, the “flow of funds,” for systematic and consistent organization of the data, classified both by sector of the economy (households, nonfinancial business, governments, financial institutions and so on) and by type of asset or debt (currency, deposits, bonds, mortgages, and so on). Although many people hope that this organization of data will prove to be as powerful an aid to economic understanding as the national income accounts, this hope has not yet been fulfilled. Perhaps the deficiency is conceptual and theoretical; as some have said, the Keynes of “flow of funds” has yet to appear.

– James Tobin in Introduction (pp xii-xiii) in Essays In Economics, Volume 1: Macroeconomics, 1987.

After having written a fantastic book Macroeconomics with Francis Cripps in 1983 and which has connections with the flow of funds, Wynne Godley thought he had to try hard to unify (post-)Keynesianism and the flow of funds approach which James Tobin was trying. Wynne Godley had the advantage of being close to Nicholas Kaldor who very well understood the importance of Keynes and was himself an economist of Keynes’ rank. Godley also had the advantage of having worked for the U.K. government and doing analysis using national accounts data and advising policy makers. Wynne Godley is the Keynes of “flow of funds” which Tobin was talking about!

A recent blog post by Matias Vernengo on Wynne Godley is extremely well-written.

In his later years (and his best), Wynne Godley worked with Marc Lavoie, one of the faces of Post-Keynesianism and one who had previously made highly original contributions to Post-Keynesianism and this led to the book Monetary Economics. Marc’s earlier work was also highly insightful and he highlighted – in the spirit of Morris Copeland – how poorly money is understood by economists in general and it was natural he and Wynne would meet and work together.

One of the things about Wynne Godley’s approach is how to combine abtract theoretical work and direct practical economic issues. This actually led him to warn of serious deflationary consequences of economic policy in fashion before the crisis.

Lance Taylor (in A Foxy Hedgehog: Wynne Godley And Macroeconomic Modelling) had a nice way to describe Wynne Godley:

Wynne has long been aware of the stupidity of models when you ask them to say something useful about practical policy problems. He has spent a fruitful career trying to make models more sensible and using them to support his policy analysis even when they are obtuse. As we have seen, this quest has led him to many foxy innovations.

But there is an enduring hedgehog aspect as well. Wynne has focused his energy on combining the models with his acute policy insight based on deep social concern to build up a large and internally coherent body of work. He has disciples and is widely influential. One might wish that he had pursued some lines of analysis more aggressively and perhaps put a bit less effort into others. And maybe not have written down so damn many equations. But these are quibbles. His work is inspiring, and will guide policy-oriented macroeconomic modellers for decades to come.

In this post, I have tried to provide the reader with references to go and verify how flow of funds1 cannot be separated from Keynesian Economics – Keynesian approach in the original spirit of Keynes, not some bastartized versions. It is as if they were made for each other2. While it is true that like other sciences, Macroeconomics is always work in progress, it doesn’t mean one should bring fashions such as inter-temporal utility maximising agents (read: future knowing economic actors) in the approach which Paul Krugman prefers.

1My usage of “flow of funds” is more generic than the usage which distinguishes income accounts and flow of funds accounts and hence my usage is for both.

2The ties between the flow of funds approach and Post-Keynesiansism is argued in Godley and Lavoie’s book Monetary Economics from which I have borrowed a lot.

Correction

I am mistaken about Jonathan Schlefer’s background. He is in academics.

The Rate Of Saving In Wynne Godley’s Models

In Krugman’s blog post which is dismissive of Wynne Godley’s work (referred in my previous post) he (Krugman) makes the following claim:

First involved consumption spending. Conventional Keynesian consumption functions suggested that the savings rate would rise as incomes rose — and this wasn’t just the Keynesian interpreters, Keynes himself made the same claim.

which shows that Krugman has less clue about what he talks. Funny, the profession is ruled by clowns like him.

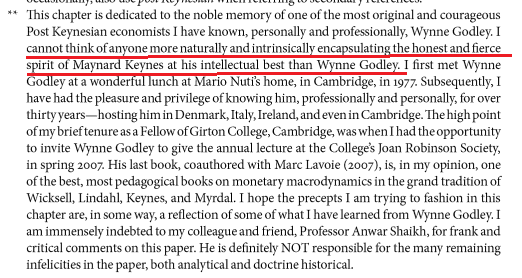

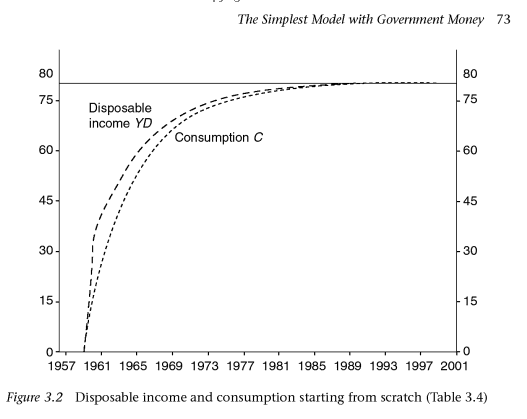

In Wynne Godley’s models, there is a propensity to consume out of income and out of wealth – represented in his models by the parameters α1 and α2 and the rate of saving in any period is given by the model. So in the simplest model – for example in Godley’s book with Marc Lavoie Monetary Economics, the rate of saving can has the following dynamic:

(image screenshot via amazon.com “Look Inside”)

(Note: In the above model, money is the only asset). This is starting from scratch but similar behaviour can be seen if one starts with some initial self-consistent configuration.

This is contrary to what Paul Krugman claims of Keynesian models. The above shows how the rate of saving first rises and then starts to fall and this whole adjustment will happen with a time lag given by a “stock-flow norm” and can be fast.

The reason it happens is simple. It is clear Krugman doesn’t realize the underlying stock-flow dynamics. As households’ saving and income rises because of a rise in government expenditure, they are also accumulating wealth. So a scenario where saving rises forever is meaningless because they would start consuming from their wealth as well.

Krugman continues:

This, in turn, led to predictions of rising savings rates after World War II, and hence a persistent shortage of demand — hence the secular stagnation theory briefly prominent. (There was even an early Heinlein novel built in part around the secular stagnation theory. As I recall, it was pretty bad.)

which is quite wrong – as stock-flow consistent dynamics suggests otherwise.

I’ll hold it to make any generic statements but it is clear that Krugman doesn’t know a thing or two about Keynesian Macroeconomics 🙂

*Many times standard textbooks use a Keynesian consumption function of the form

C = α0 + α1·YD

where C is the consumption, and YD is the disposable income.

It is then easy to see that C/YD decreases with YD and this is what Krugman is talking of.

However only slight improved modification where the consumption function depends on wealth as well leads to a different behaviour as highlighted in the main text. So it is strange Krugman dismisses consumption functions and instead talks of “failures that it seemed could have been avoided by thinking more in maximizing terms” !

*I thank Nick Edmonds in pointing this out.

Wynne Godley: The Keynes Of Flow Of Funds

Monetary and financial data, so far as they are based on institutional balance sheets and prices in organized markets, are abundant. Modern machines have made it possible to improve, refine and expand the compilation of these data, and also to seek empirical regularities in financial behavior in the magnitude of individual observations. On the aggregate level, the Federal Reserve Board has developed a financial accounting framework, the “flow of funds,” for systematic and consistent organization of the data, classified both by sector of the economy (households, nonfinancial business, governments, financial institutions and so on) and by type of asset or debt (currency, deposits, bonds, mortgages, and so on). Although many people hope that this organization of data will prove to be as powerful an aid to economic understanding as the national income accounts, this hope has not yet been fulfilled. Perhaps the deficiency is conceptual and theoretical; as some have said, the Keynes of “flow of funds” has yet to appear.

– James Tobin in Introduction (pp xii-xiii) in Essays In Economics, Volume 1: Macroeconomics, 1987.

[bolding: mine]

Paul Krugman writes in his blog responding to a recent Times article on Wynne Godley with a dismissive tone with mischaracterisation on saving etc. He writes:

But it is kind of funny to see a revival of old-fashioned macro hailed, at least by some, as the key to a reconstruction of the field.

Strange. First it is the story of a journalist from NYT who presented it the way it was. The NYT article was fine – what more can we ask from the journalists? But the funny thing is Krugman’s blog post itself which appeals to Friedmanism. Even funnier is the fact that Paul Krugman himself has turned to Keynesianism in recent times and talks about Michal Kalecki but when it suits his purpose, he dismisses Godley’s ideas as old fashioned!

Paul Krugman in his debates with heteredox economists has been exposed with his poor understanding of the nature of money. Wynne Godley’s approach on the other hand goes into a detailed look at the nature of money using the flow of funds among other things in a Keynesian way.

Now Krugman’s post is hardly a critique of any sort to deserve a response. But I thought quoting James Tobin is a good way to advertise Wynne Godley’s work because he has achieved what Tobin dreamed of and could not do it himself.

Also Wynne’s own idea about his work and aims can be seen from his writing in his article Keynes And The Management Of Real National Income And Expenditure, (in Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983):

… I have been forced to the conclusion that Keynes was a long way from achieving a coherent theoretical basis for maintaining them [correct ideas], and largely for this reason, his ideas have proved very vulnerable to the attacks from many different directions to which they have been subjected, particularly in the last fifteen years.

Wynne Godley’s work lays the foundation for Keynesian Economics. And Wynne Godley is the Keynes of flow of funds.

Correction: I am mistaken about Jonathan Schlefer’s background. He is in academics.

NYT On Wynne Godley

There’s a nice new article on Wynne Godley today in The New York Times.

An interesting thing in the article is the mention of intuition via models while mentioning his book Monetary Economics.

Why does a model matter? It explicitly details an economist’s thinking, Dr. Bezemer says. Other economists can use it. They cannot so easily clone intuition.

That is so right. The models in the books of Wynne Godley – both Monetary Economics with Marc Lavoie and Macroeconomics with Francis Cripps give a good idea about the authors’ intuitions. Of course, needless to say the man was bigger than his models.

Holier Than Tobin?

It sometimes happens that important insights of great contributors to an academic field are missed. One of the most important things in Monetary Economics is Tobin’s asset allocation theory which although is well known is sometimes poorly understood.

James Tobin (Source: Econometric Theory)

James Tobin (Source: Econometric Theory)

But sometimes a holier-than-thou attitude can lead one to miss an important and insightful aspect of a work.

The blogger Winterspeak – well aware of some of Tobin’s work such as his paper Commercial Banks As Creators Of “Money” from 1963 has written as post A Bank is not a Financial Intermediary and concludes that

… This then is the conceptual fallacy at the heart of academic macro and what it thinks about banks, and it goes at least all the way back to 1963.

Winterspeak is stuck on a quote from Tobin-Brainard paper (1963) which says:

…the essential function of financial intermediaries, including commercial banks, is to satisfy simultaneously the portfolio preferences of two types of individuals or firms. On one side are borrowers, who wish to expand their holdings of real assets… On the other side are lenders who wish to hold part or all of their net worth in assets of stable money value with negligible risk of default.

This is also repeated in Tobin’s Commercial Banks As Creators Of “Money” which obviously states explicitly that loans create deposits and that the money mutliplier view is highly inaccurate:

According to the ‘new view’, the essential function of financial intermediaries, including commercial banks, is to satisfy simultaneously the portfolio preferences of two types of individuals or firms. On one side are borrowers, who wish to expand their holdings of real assets – inventories, residential real estate, productive plant and equipment, etc. – beyond the limits of their own net worth. On the other side are lenders, who wish to hold part or all of their net worth in assets of stable money value with negligible risk of default. The assets of financial intermediaries are obligations of the borrowers – promissory notes, bonds, mortgages. The liability of financial intermediaries are the assets of the lenders – bank deposits, insurance policies, pension rights.

Winterspeak is adamant about the usage of the phrase “intermediary” and that since banks create deposits out of thin air, they shouldn’t really be called intermediary and that Tobin’s views are equivalent to the loanable funds view. For the first part – maybe but Winterspeak seems to crucially miss out the mediating role played by banks in the portfolio allocation decisions of wealth owners such as households. See my comments in that blog.

First it is crystal clear that Tobin knows loans create deposits. Second, he presents a “new view” in which the distinction between “money” and “bonds” is blurred and this led him subsequently to his asset allocation theory. It is true that Tobin’s model was far from complete and this was improved substantially by Wynne Godley, but nevertheless Tobin’s insights were wonderful and the work of a genius.

Perhaps I would have worded what Tobin wrote differently if I were to teach this but this is just a matter of emphasis.

Perhaps “the essential function” is better worded with “an essential function” so that the reader doesn’t take it to mean that the concept I will come to, isn’t taken to mean “the only function” or “the most essential function”.

The mediation role played by banks is related to the super-version of “loans create deposits” – asset purchases by banks also create deposits.

So when a bank purchases say a government bond from a household (or a mutual fund selling in response to redemptions by a household), banks create more deposits in the process. In the opposite case, there is a destruction of deposits.

Now suppose for some reason – such as improved animal spirits of entrepreneurs, firms borrow more from banks and the expenditures transfers funds to households. Coincidentally – for different reasons – households wish to hold less of their wealth in deposits and more in bonds or other securities. There is now a discrepancy and it is reconciliated by banks standing ready to sell bonds to households. This decreases the stock of money (monetary aggregate) in existence so that there is no discrepancy at all. There is of course another way in which this may happen – i.e., by price changes (of financial secruities and not that of goods and services) bringing supplies equal to demand but this needs a full course on asset allocation theory discovered by nobody else than James Tobin himself!!

Of course there are other ways. There is the reflux mechanism and more complicated mechanisms involving asset allocation theory such as higher issuance of equities by production firms. In the reverse case when households desire to hold more of their wealth in deposits, firms may need to borrow more from banks so that the “supply” of money is equal to the “demand”.

In contrast there is the Monetarist hot potato process which mainly relies on prices changes of goods and services. In ideas such as the asset allocation theory including the mechanism of the mediating role of banks is a blow to the Monetarist hot potato.

Of course there is the notion of convenience lending – one favoured by Basil Moore – in which household volitionally hold bank deposits non-volitionally but it is too artificial.

This mediating role of banks (and not the most important if you like) is also endorsed by some Post-Keynesian authors such as Wynne Godley and Nicholas Kaldor.

In an article In his essay Keynes And The Management Of Real Income And Expenditure, (in Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983), Wynne Godley says (p 151):

Even though I am not going in detail into monetary mechanisms it is worth drawing attention to the fact that the commercial banks’ role, apart from creating credit to finance certain kinds of expenditure, is to mediate the non-bank private sector’s portfolio choice, given the income flows and the central authorities’ funding policy.

Nicky Kaldor’s The Scourge Of Monetarism (Oxford University Press, 1982) is more clearer than simply stating:

As it is, a highly developed banking system already provides such facilities on an ample scale, since it is prepared to accommodate the public’s changing demand between different types or financial assets by altering the composition of the banks’ assets or liabilities in a reverse direction. If the non-banking public wishes to switch its holding of gilts for interest-bearing bank deposits, the banks are ready to supply such deposits at the minimum of inconvenience, and at the same time to place their surplus funds into the gilts which were previously held by the public. Similarly the banks provide easy facilities to their customers for switching balances on current accounts into interest-bearing deposit accounts, or vice versa. Hence, while the annual increment in the total holding of financial assets of the private sector (considered as a whole) is nothing more than the mirror-image of the borrowing requirement of the public sector (in a closed economy at any rate), neither the Government nor the banks can determine how much of this increment will be held in the form of cash (meaning notes and current deposits) and how much in the near-equivalents to cash (such as interest-bearing demand deposits) or in various forms of public sector debt. Thus neither the Government nor the central bank can control how much or the total financial assets the public prefers to hold in the form of ‘money’ on one particular definition or another.

Again in 1997 in Money Finance And National Income Determination Wynne Godley repeats himself although criticising Tobin but nevertheless realising the importance of his work – this time writing an explicit model for the whole thing which incorporates Tobin’s ideas:

… I am saying that (within strict limits e.g. concerning credit-worthiness) banks respond passively to the needs of business for loans and to the asset allocation activities of households (as well as providing the means of payment).

Conclusion

It is true that PKE authors and bloggers do have a much better understanding of monetary matters than mainstream economists but in trying to emphasise this point, sometimes they miss out on important matters. There is no need to say (as Winterspeak says “Tobin … sees … [banks as] something which brings efficiency and eases friction between the actual lender and borrower.”) especially when Winterspeak doesn’t seem to understand the mediating role of banks in the portfolio allocation decisions of financial asset owners which really has less to do with any “friction”. Perhaps the word intermediary is not the best but it is a minor point. In fact the ideas of the 1960s and later are missed by younger ones.

Thomas Palley On International Coordination

Thomas Palley has a new article Coordinate Currencies or Stagnate on international coordination of exchange rates. (h/t Matias Vernengo). He has a nice small critique of the Chicago school according to which “market forces” work toward resolving imbalances.

It is great such a thing has been raised because the importance of policy coordination (in general – monetary, fiscal and exchange rates) is often forgotten.

In an article Agenda For International Coordination Of Macroeconomic Policies, Tobin wrote [1]

Coordinate policies! So economists urge governments. Financiers, journalists, pundits, politicians take up the cry. Central bankers and finance ministers agree, as do presidents and prime ministers. They meet, they talk, they announce progress. It turns out to amount to very little…

But the global imbalance has worsened and it has now created a situation in which such coordination is more badly needed.

Wynne Godley had been warning of such things in the 2000s. In a 2005 article [2] with his collaborators, he wrote:

A resolution of the strategic problems now facing the U.S. and world economies can probably be achieved only via an international agreement that would change the international pattern of aggregate demand, combined with a change in relative prices. Together, these measures would ensure that trade is generally balanced at full employment…Those hoping for a market solution may be chasing a mirage.

I have also found the last words in academic literature very insightful [3]:

… It is inconceivable that such a large rebalancing could occur without a drastic change in the institutions responsible for running the world economy—a change that would involve placing far less than total reliance on market forces.

Time will tell how right he was 😉

References

- James Tobin, Agenda For International Coordination Of Macroeconomic Policies, Ch 24, p 633, Essays In Economics, Volume 4: National And International, The MIT Press, 1996.

- Wynne Godley, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Claudio Dos Santos and Gennaro Zezza – The United States And Her Creditors: Can The Symbiosis Last?, Levy Institute Strategic Analysis, September 2005. Link

- Wynne Godley, Dimitri Papadimitrou and Gennaro Zezza – Prospects For The United States And The World – A Crisis That Conventional Remedies Cannot Resolve, Levy Institute Strategic Analysis, December 2008. Link

Kenneth Rogoff Is Back With Another Sneaky Article

Kenneth Rogoff is back with more unscholarly stuff.

In a new article for Project Syndicate Europe’s Lost Keynesians, Rogoff subtly tries to belittle Keynesians and Keynes himself.

According to him,

The eurozone’s difficulties, I have long argued, stem from European financial and monetary integration having gotten too far ahead of actual political, fiscal, and banking union. This is not a problem with which Keynes was familiar, much less one that he sought to address.

Now, Keynes himself was aware of problems that arise in an open economy, the above quote tries to mislead the readers into thinking that neither Keynes nor his followers were aware of the problem.

It was in fact Keynesians who warned about the troubles the Euro Area would face. Last year, I dug out an article by Nicholas Kaldor from 1971 which shows how highly prescient he was. The article The Dynamic Effects Of The Common Market first published in the New Statesman, 12 March 1971 and also reprinted (as Chapter 12, pp 187-220) in Further Essays On Applied Economics – volume 6 of the Collected Economic Essays series of Nicholas Kaldor is written as if it was written yesterday!

Here is from the article:

… Some day the nations of Europe may be ready to merge their national identities and create a new European Union – the United States of Europe. If and when they do, a European Government will take over all the functions which the Federal government now provides in the U.S., or in Canada or Australia. This will involve the creation of a “full economic and monetary union”. But it is a dangerous error to believe that monetary and economic union can precede a political union or that it will act (in the words of the Werner report) “as a leaven for the evolvement of a political union which in the long run it will in any case be unable to do without”. For if the creation of a monetary union and Community control over national budgets generates pressures which lead to a breakdown of the whole system it will prevent the development of a political union, not promote it.

[italics in original]

To read more excerpts from the article please read the following two posts from this blog:

In fact Nicholas Kaldor had already figured that the kind of fiscal union Europeans were thinking was a kind of a pseudo fiscal union – as can be seen by reading the excerpts (see the second post above).

Also Wynne Godley – a close friend of Nicky Kaldor – also reminded the dangers of the Maastricht Treaty in his 1992 LRB article Maastricht And All That.

Kenneth Rogoff is being ignorant and unintellectual. First he writes as if Keynesians had no clue about the problem and secondly he is unaware of the fact that the kind of fiscal union in talks in Europe is a pseudo fiscal union which Keynesians such as Nicholas Kaldor have pointed out since 1971.

He ends the article by saying

… there still will be no simple Keynesian cure for the single currency’s debt and growth woes.

which is ignorant. The solution if it comes about is Keynesian and Keynesians had warned it will be difficult to resolve a future crisis because of political difficulties which arise.

Rogoff’s attitude is that of a person who ignores the doctor’s warning continuously and then ridicules the doctor when medical problems finally appear. Just like the cure will come from the doctor, so will the resolution via Keynesianism.

Endogeneity, Exogenous, Et Cetera

Louis-Philippe Rochon and Sergio Rossi have a very interesting article Endogenous Money: The Evolutionary Versus Revolutionary Views in the Review Of Keynesian Economics. I think it was written many years back and was in an unpublished form and has been published now. It is a nice critique of views of some Post-Keynesians such as Victoria Chick and also others such as Basil Moore. For instance, the paper quotes Moore’s view from 2001:

[w]hen money was a commodity, such as gold, with an inelastic supply, the total quantity of money in existence could realistically be viewed as exogenous.

Click the image to visit the ROKE website.

There are also some nice articles in a recent issue of JPKE on neoliberalism and the financial crisis.

Some gossip: The JPKE was initially supposed to have been called Journal of Keynesian Economics but it didn’t make it because the acronym would have been JOKE.

Also, Jayati Ghosh has written an excellent blog article on Thatcherism – the ‘triumph of private gain over social good’ (borrowing words from her).

Matias Vernengo has a recent blog post on the persistence of poverty in the United States. Which reminds me of an interview clip of Anwar Shaikh titled “The Sin Of Our Era”:

click to watch the video on YouTube

Back to formal matters.

What does it mean when an economist says words such as “endogenous”, “exogenous”? Most of the times, economists – mainstream economists – themselves confuse these terms and hence you see a lot of usage of these words in Post-Keynesian economics.

I was reading an article on econometrics by Fischer Black (of the Black-Scholes fame) titled The Trouble with Econometric Models

An exogenous variable is supposed to be a causal variable, if the structure of a model has economic meaning. In fact, it is usually just a variable that is put on the right-hand side of equations in a model, but not on the left-hand side.

Similarly, an endogenous variable is supposed to be a caused variable. In fact, it is usually just a variable that shows up at least once on the left-hand side of an equation

which is fair but there exists another language.

There is however another usage – that is in the control sense.

In an outstanding paper Federal Reserve “Defensive” Behavior And The Reverse Causation Argument, Raymond E. Lombra and Raymond G. Torto point out the following in the footnote:

Apparently no generally accepted concept of an endogenous money stock (or monetary base) has been defined. In statistical theory a variable is endogenous if it is jointly determined with other variables in the system. However, many monetary theorists have chosen to call a variable endogenous only if its magnitude is not under the control of policymakers. Such semantic problems have undoubtedly prolonged this debate.

For the money stock measure such as M1, M2 etc., there shouldn’t be any confusion. The trouble arises for things such as interest rates. For example, some economists may say that if inflation rises, the central bank may/will raise the short-term interest rate and it is endogenous while others will say it is up to the central bank to decide how much to change the interest rate, if at all. Such things lead to a lot of debate.

I like the latter usage (the control sense) but I think it is difficult to exclusively have the same usage.

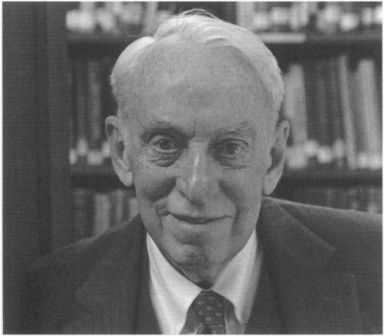

The word “control” is also misunderstood. Here is a fine article on Wynne Godley in The Times from 16 June 1978 where he details on how misunderstood the word is:

(click to expand)